Like it or not, citizens of the world are participating in a giant, unprecedented, ‘natural experiment’ – the Covid pandemic. Enforced changes in our everyday behaviour have had multiple impacts across markets and categories. Some of these effects are more predictable, and well-documented: because going to the shops was difficult (or the shops were shut), most of us turned to shopping online for everything from clothes to food to alcohol.

‘Natural experiments’ are, by their nature, naturally-occurring events whereby we can clearly establish a baseline or control scenario (ie how society operated prior to Covid) and compare behaviour then with what’s happening now. The fundamental advantage of natural experiments is that you can observe differences between the ‘before’ situation and the ‘after’ situation, and be more confident that changes observed (in this case, a global pandemic) are connected with this change in conditions.

However, simply concluding that a change is “because of Covid” begs further questions: how has Covid effected change in behaviour? Why has the behaviour changed? Once Covid becomes manageable, will that change be reversed? And why, in some markets, are we seeing different reactions to others?

This last question is particularly pertinent within the wine category. In certain markets, wine sales grew as a result of Covid – wine surged in 2020 in markets such as Brazil and South Korea, as well as ticking upwards in more mature markets such as Sweden, the US, UK and Germany. In the latter two markets, volume growth in 2020 reversed long periods of volume decline. However in the same period, wine went into reverse in markets as diverse as China, Japan, while declining volume markets such as Spain and France saw existing rates of volume decline accelerate. In France, for example, wine volumes declined -3% between 2018 and 2019, but the category declined by -9% between 2019 and 2020, according to IWSR data.

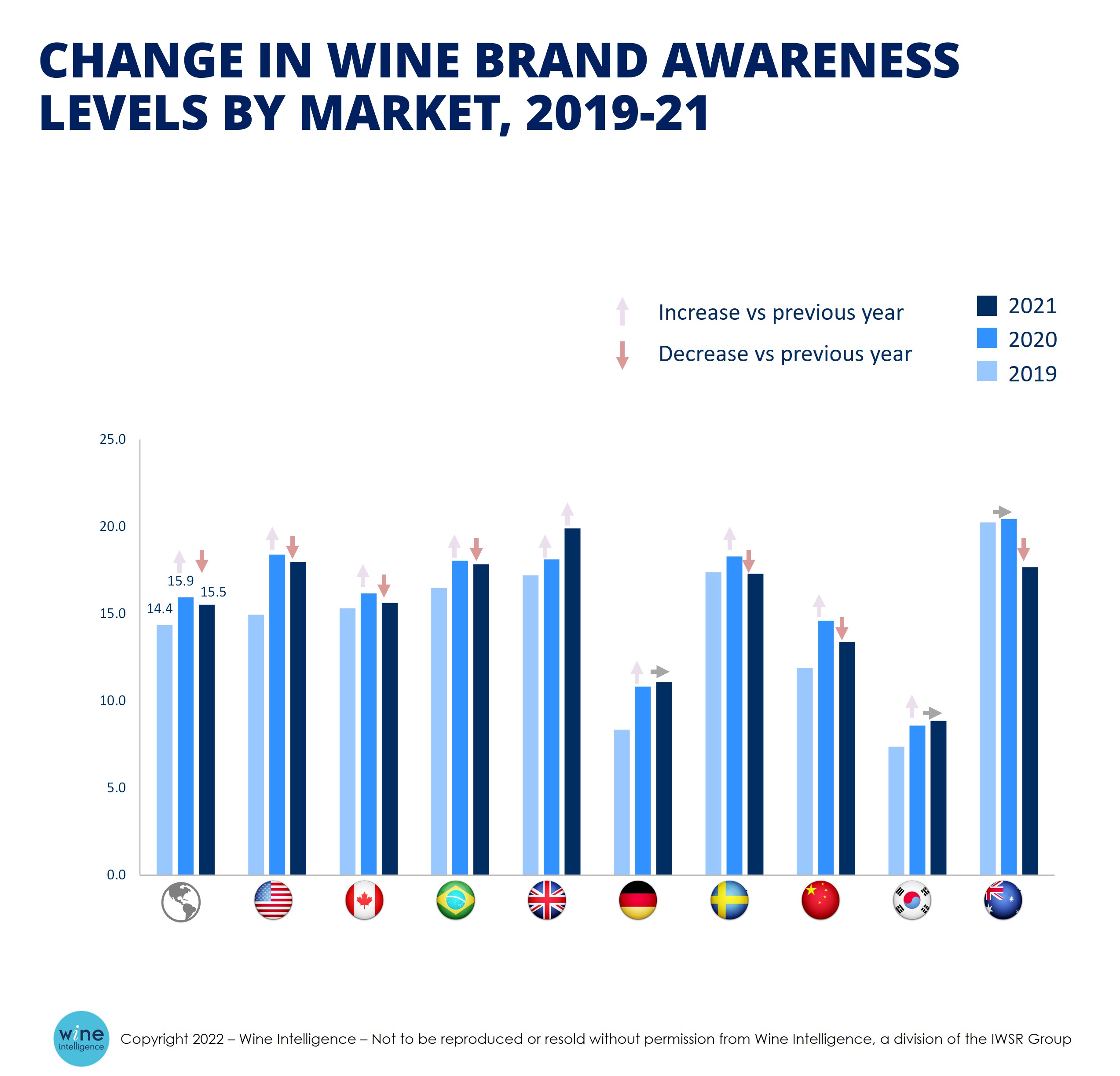

The complexity grows as we observe that the same macro change (Covid) has had different effects across markets, and therefore on consumers’ knowledge, confidence and involvement levels with wine. Over the course of the pandemic, the ability of consumers to recall things such as varietals, wine brands and regions of origin in our surveys have shown across-the-board declines in some markets, while showing growth, or little change, in others.

Based on observing these changing relationship with wine, and in particular wine brand, we firstly need to eliminate the possibility that there has been a data error. Consistent data collection methods have been used by Wine Intelligence for over a decade, and were not changed during the pandemic, with the core questions asked remaining consistent. Our sampling process is quota-controlled, so that we can ensure that the wine drinkers we speak to are representative of the wine drinkers of a particular nation.

So, if our investigation of the data indicates that the data is both reliable and valid, what’s going on to drive the observed changes with the wine category?

Our data shows that the reduction in awareness of wine brands is not translating into reduced purchase incidence – either purchase frequency or the volume of each brand purchased. In several markets, conversion rates for brands (the proportion of wine drinkers who are aware of a given brand who have purchased it in the past 3 months) have in fact risen.

To help understand what’s happening in the wine category, we need to recognise that multiple social, political, economic and supply chain forces are at work. Our analysis suggests that three factors are at work:

- Comfort levels surrounding daily activities

- Availability and accessibility of retail channels

- Underlying social needs and cultural norms

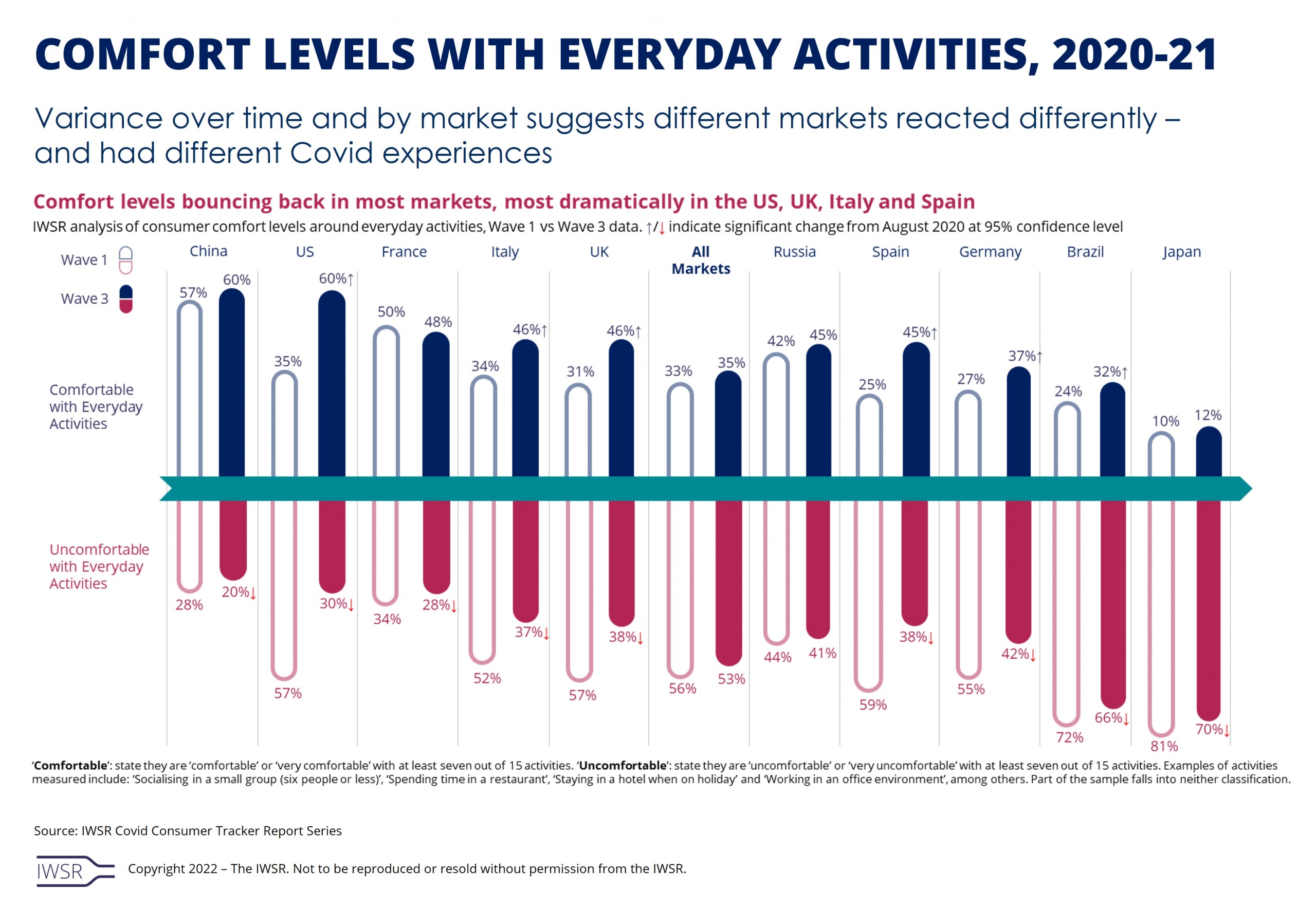

Comfort levels surrounding daily activities

The IWSR Covid Tracker consumer insights (published in 2021) for total beverage alcohol measured consumer confidence in 10 key beverage alcohol markets, based on how comfortable consumers were with everyday activities during Covid, such as going to work, seeing friends, visiting shops, and attending events. In August 2020, comfort levels were relatively low, typically coinciding with the first wave of Covid. These levels hit a low in December 2020 (Covid’s second wave in most markets), and then bounced back in July 2021 (see chart). More surprising was the variance in comfort levels between markets: US consumers were cautious in August 2020, but much more comfortable by July 2021; Chinese consumers reported consistently high comfort levels; those in Japan consistently very low comfort levels. In all markets measured, older consumers were much more likely to be uncomfortable compared with younger legal-drinking-age consumers. In markets where there was a stronger positive correlation between age and wine drinking, such as the UK, we found that wine drinkers were on balance less comfortable with visiting shops than non-wine drinkers.

Availability and accessibility of retail channels

The loss of footfall in major shopping locations around the world during Covid is now well documented and also available in near-real time thanks to Google Community Mobility Reports. Using this data, journalists at The Conversation showed that footfall in major CBDs in Australia fell dramatically during the first Covid lockdown and had recovered in some cities by October 2020. However, those cities suffered prolonged periods of lockdown, such as Melbourne, saw activity decline by 85% compared with a baseline of February 2020. This unprecedented interruption to normal shopping patterns, combined with comfort level variation, appears to have had a profound effect on shopping behaviour across all categories, and wine is no exception. Wine Intelligence’s interview research for our 2021 Portraits consumer segmentation reports in UK and US reported increasing nervousness around spending time in wine shops, and the difficulty around finding shop staff to interact with, partly driving the growing preference for shopping online.

Based on these factors, we can hypothesise that the preference for online, plus loss of footfall and dwell time in physical retail, has affected relationships with wine brands, with the nature of the effect dependent on the availability and accessibility of retail channels. Take two examples: the online shop and the ‘Grab-and-go’ physical retail mission to a local shop. Both would be substitutes for a longer, in-person shop at a major supermarket, and in both cases the choice of retail outlet available would be a major factor in the type of wines purchased. In the case of the online shop, the offering could be omnichannel (a supermarket website), a specialist retailer, or a producer, depending on where the consumer lived and what regulations might govern online retail. In each case, the types of product on offer would be different to the traditional supermarket, and the way in which one shops online – less visual, more factual – would also be an influence. In grab-and-go convenience store missions, a consumer would tend to focus more on the familiar and/or obvious at the expense of the new and hard-to-find. Availability, as dictated by retailer ranging policies, would be the obvious constraint here.

How might this vary by market? For instance, UK supermarkets, and their branded small-format convenience store incarnations, tend to do more block-branding and end-caps within a broad range of source countries and in the case of the convenience sector, offer a very constricted range of well known brands plus own label. Major Australian retailers tend to be devoted to domestic production or wines from New Zealand, and offer a greater depth of range within a sub-region. In the US, a patchwork of varying state-level regulations makes broad-brush comparisons harder, but even here shoppers have flocked to online options, be they specialist retail, omnichannel, or direct from producer. In Sweden, a population locked down from overseas travel (and therefore travel retail) was forced to shop in Systembolaget.

Underlying social needs and cultural norms

If shopping patterns, and what is available in retail, are a big influence on what is purchased, underlying consumer needs also play a part. With wine drinkers largely confined to their homes for long periods, and denied their normal pattern of socialising, it is therefore likely that their normal connections to wine brands have been disrupted. Studies have pointed to the power of emotional connection to increase the effectiveness of a brand’s connection with consumers. A social occasion in another person’s home or in on-premise is a more emotionally powerful event compared with, say, sitting in front of the TV on your own. It is also opportunity to notice what other people are doing and discover – what fashions being worn, what home furnishings, what food types, and what drinks are being drunk. With fewer opportunities to see new brands / remind themselves of known brands outside their normal purchase pattern, one could posit that disruption to normal social behaviour arising from Covid has had an impact on this brand connection vector.

Additionally, the reduction in social occasions to stimulate connection with the wine category would be more acute in people who are relatively new to the category, and are still in ‘discovery’ mode. A consistent finding from Wine Intelligence consumer tracking is that older wine drinkers are less likely to socialise in groups compared with younger wine consumers. Another consistent finding is that older drinkers tend to have more deep-seated category knowledge, which is not surprising given their category experience.

Clearly other influences are also playing their part in this giant natural experiment. The fundamental disruption of daily life has yielded a spectrum of reactions, including changes in the way we feel about our health, wellbeing, our ability to control things, the kind of work we do, and how we do that work. Brands that have succeeded in this era have done so because they solve problems in this new equilibrium. These could be practical – I can’t go to the gym so I will buy a Peloton – or commercial – I can’t go to the office so I will use Zoom. Where wine brands fit into this picture depends on their pre-existing relationship with a consumer, and how that consumer is now navigating their Covid era world.

You may also be interested in reading:

- New behaviours drive wine market opportunities in the UK

- Which key macro factors are driving the global wine industry in 2021?

- Millennials drive the sparkling wine category

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!